Climate and energy issues are clearly very important to many voters, even if what the parties say on these issues may be unlikely ultimately to be a decisive factor in determining the outcome of the election. This is the first UK general election to take place since:

- the world reached 1 degree C of warming from pre-industrial levels in 2017;

- the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued a report in October 2018 showing the importance of keeping global warming to 1.5 degrees C – which probably means achieving net zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050; and

- the UK Climate Change Act 2008 (CCA 2008) was amended (in June 2019) to reflect a version of that 2050 net zero target (UK net emissions, as defined in that legislation, are to be “at least 100% below” 1990 levels by 2050).

The target

The new CCA 2008 target was set on the recommendation of the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) in a report of May 2019. The CCC pointed out that:

- current policies across the full range of relevant sectors (including energy, transport, agriculture and the built environment) are unlikely to deliver even the 80% reduction on 1990 GHG emissions required by the CCA 2008 in its original form;

- the way that the CCA 2008 regime currently measures net emissions does not take account of emissions for which the UK economy is responsible but which are released into the atmosphere outside its borders (emissions from international flights and shipping to and from UK destinations and from e.g. factories in other countries that make goods consumed in the UK), but it does take account of UK carbon offsetting – so far the CCC’s recommendations for changes in these areas (see the report and also here) have not been implemented;

- it should be possible to achieve a net zero GHG emissions target by 2050 (even one that was more strictly defined to include e.g. international aviation and shipping emissions), and to do so at no greater net cost than achieving the previous 80% reduction target (up to 2% of GDP);

- this will, however, require massive efforts on the part of government, a range of industries, and individual consumers.

The CCC divides the additional efforts on top of current policies into two categories, of “further ambition” and “speculative” options.

- In the former category are things like achieving 90% low carbon heating (current level – 4%); quadrupling low-carbon power generation capacity; having all new cars and vans on the road electric by 2030 or 2035 rather than the current target of 2040; installing hundreds of thousands of public EV charging points; and a 20% reduction in consumption of beef, lamb or dairy. Carbon capture, usage and storage (CCUS) is seen as a crucial technology, supplying some of the flexible low carbon power; helping to halve emissions from industrial process heat; supplying hydrogen to use as a substitute for hydrocarbons in other industrial processes and powering trains and HGVs; and helping to generate negative emissions by combining the carbon neutral use of sustainable biomass to generate power with capture and storage of the CO2 emitted (BECCS).

- All the “further ambition” options together would get us to a 96% GHG emissions reduction by 2050. We would need to make some of the “speculative options” work to achieve the rest. They include deeper reductions in meat and dairy consumption (50%); direct air carbon capture and storage (DACCS, at present largely experimental); limiting the increase in passenger flights to 20-40% above 2005 levels; and using synthetic carbon-neutral fuels to power aviation (a blend of hydrogen and CO2 captured from the air using DACCS).

Common areas of energy and climate policy discussion

It is interesting to see how far each party is prepared to go, in manifestos that to a greater or lesser extent are aiming to sell themselves to a wide electoral audience, in confronting some of the hard choices that future governments in the UK and elsewhere will have to face if they are to meet net zero targets.

In the table below we have summarised the policies of six parties relating to energy and climate matters, as stated in their respective 2019 manifestos. We have selected the Conservative, Labour, Liberal Democrat, Green and Scottish National Parties, and Plaid Cymru (the Party of Wales). All were represented in the previous House of Commons, and all represent constituencies within the GB electricity and gas markets (Northern Ireland’s energy markets being separate).

Energy is not a ring-fenced area of policy. It has a major interface with transport, for example. And not every party covers exactly the same areas in its manifesto discussion of energy and climate change matters. The table focuses on what may be thought of as core energy areas, on which all six manifestos put forward policies. Below the table, we draw out some of the areas that are more distinctive to one or more parties.

Summary table of key energy and climate policies discussed in the six parties’ manifestos

| Net zero headline targets | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservatives | Labour | Lib Dem | Green | SNP | Plaid Cymru |

| Continue towards current target of carbon neutral by 2050. | Aim to make net zero by 2030 as achievable as possible, following their previously published 30 by 2030 report. | Aim for carbon neutrality by 2045, with emissions halved by 2030. | Committed to aim of carbon zero by 2030. | Already committed to net zero by 2045; further aim of 75% reduction in emissions by 2030. | At least 55% emissions reduction by 2030, aiming for net zero by 2030. |

| Net zero headline targets | |||||

| Conservatives | Labour | Lib Dem | Green | SNP | Plaid Cymru |

| Continuation of the Future Homes Standard policy; consultation on existing homes and public buildings to be produced in early 2020. Also committed to investing £9.2 billion in energy efficiency in dwellings and public buildings, support the creation of new kinds of homes with low energy bills. | Aim to make all newly built homes carbon neutral by 2030 and upgrade almost all 27 million homes to highest energy efficiency standards.

|

Retrofit 26 million homes by 2030 and retrofit all fuel poor homes by 2025. Future-proof all newly built homes. Every home built after 2021 to adhere to high energy efficiency targets. | 100,000 new homes for social rent per year to be built to Passivhaus standard, improve every UK home to be insulated using sustainable materials, with additional deep retrofitting of 10 million homes. Improve 1 million existing homes/ other buildings per year to reach highest standards (above EPC A grade). | Greener tax deal for heating and energy efficiency improvements in homes and businesses, with tax incentives to enable people to make the switch to low-carbon heating at a lower cost. Ensure that all new homes must use renewable or low carbon heat by 2024. | Roll out a £3 billion home energy efficiency programme. |

| Renewables | |||||

| Conservatives | Labour | Lib Dem | Green | SNP | Plaid Cymru |

Planning to continue the shift towards renewables at the pace currently exhibited in government, with some slightly more ambitious targets for investment:

|

90% of electricity and 50% of heat to be produced by renewable sources by 2030.

|

Accelerate the pace at which the energy production transitions to renewable, aiming to reach 80% renewable electricity by 2030. Additional funding of £12 billion over five years for this and storage, demand response, smart grids and hydrogen. | Aiming for 100% of energy to be renewable by 2030, with 70% being provided solely by wind.

|

Aim to press government for devolution in order to have more ambitious renewables targets, such as allowing wind and solar power to bid for ‘contracts and difference’ support. Overturn existing UK government policies by e.g.:

|

Similar aims to SNP in terms of seeking own, self-sufficient renewables programme for Wales. This would see Wales become 100% self-sufficient in renewable electricity by 2035. |

| Nuclear | |||||

| Conservatives | Labour | Lib Dem | Green | SNP | Plaid Cymru |

| Continue to support nuclear energy, viewing it as an alternative to traditional fuel sources. | Want new nuclear power for energy security. | No mention of nuclear energy in manifesto. | Prohibit the construction of any more nuclear power stations. | Oppose any new nuclear power plants. | No mention of nuclear energy in manifesto. |

| Net zero headline targets | |||||

| Conservatives | Labour | Lib Dem | Green | SNP | Plaid Cymru |

| Put forward an ‘oil and gas sector deal’ to support the transition from oil and gas to a net zero economy. Fracking moratorium to continue unless science shows it is safe. | Priority for the transition away from oil and gas is the workers in this sector, which they will help through a windfall tax on companies “that knowingly damage our climate”. Ban fracking. | Ban fracking. | Want a marked transition away from the oil and gas industry which will be achieved through removing subsidies to oil and gas industries. Ban fracking. | Aim to protect jobs in the North Sea oil and gas industry, in particular by providing £12 million Transition Training Fund. Ban fracking. | Similar position to Liberal Democrats. No specific mention of the oil and gas industry, but a plan as to how it will be phased out. Ban fracking |

| Electric vehicles | |||||

| Conservatives | Labour | Lib Dem | Green | SNP | Plaid Cymru |

| Support clean transport to ensure clean air and consult on the earliest date by which sale of new conventional petrol and diesel cars can be phased out. | Strong desire to implement use of electric vehicles as commonplace. | Accelerate the transition to ultra-low emission transport through taxation, subsidy and regulation. | End the sale of new petrol and diesel fuelled vehicles by 2030 and ease transition by incentivising purchase of electric vehicles with a network of charging points. | Campaign for the UK government to bring forward plans to move the transition to electric vehicles to match Scottish target of 2032. | Start the transition towards a wholly electric fleet of public sector vehicles. |

Where do the parties’ approaches differ?

Some of the differences between the parties will be apparent from the table. But we note some further points that distinguish their approaches below.

The energy and climate change section of the Conservative manifesto is less expansive than the others. But the party is presenting itself as continuing with current government policies, presumably including the output of a large crop of recent energy-related consultations in areas such as nuclear power, CCUS and energy efficiency in buildings.

Labour’s energy policy is closely linked to its broader plans for taking certain utility industries back into public ownership, and for investing very large amounts of public money in infrastructure projects. For them, and for the Green Party, facilitating energy transition is part of a process of bringing about wider social and economic changes.

- They have proposed the creation of a National Energy Agency to own and maintain “the national grid infrastructure” and oversee delivery of decarbonisation targets, as well as new Regional Energy Agencies to replace existing distribution network operators and hold “statutory responsibility for decarbonising heat and reducing fuel poverty”. The supply businesses of the “Big Six energy companies will be brought into public ownership”.

- Their plans for very substantial public funding of infrastructure include a £400 billion National Transformation Fund, £250 billion of which will be directed to a Green Transformation Fund. Apparently in addition, a National Investment Bank and Regional Development Banks, would provide “£250 billion of lending for enterprise, infrastructure and innovation over 10 years”.

The Liberal Democrats have a number of policies focused on devolving net zero powers and responsibilities to local authorities. They would “regulate financial services to encourage green investments”; and “end support from UK Export Finance for fossil fuel-related activities”. They also focus on reducing the climate impact of aviation “by reforming the taxation of international flights to focus on those who fly the most, while reducing costs for those who take one or two international return flights per year” and “placing a moratorium on the development of new runways (net) in the UK”.

As one would expect, energy and climate change issues are perhaps most prominent and fully integrated into the overall programme for government put forward by the Green Party. As the summary table above indicates, they tend to go furthest in any given area of activity that could promote net zero: they even propose to plant more than 10 times as many trees as the next strongest advocates of this form of carbon sink (700 million as against 60 million). But perhaps the most notable feature of their manifesto in this respect is that they appear to be the only one of these parties advocating comprehensive carbon tax reform (a prospect that may be facilitated by Brexit). They would apply a carbon tax to “all fossil fuel imports and domestic extraction, based on [GHG] emissions produced when the fuel is burnt” and on “imported energy, based on its embedded emissions”, with a view to “rendering coal, oil and gas financially unviable as cheaper renewable energies take their place”. The tax would also cover “meat and dairy products over the next ten years”. Revenues would be recycled in particular ways – for example to fund a “universal basic income” and provide transitional assistance to farmers. It is to be expected that most political parties do not promote new forms of taxation in their manifestos, but the general lack of engagement with the notion of a progressive and redistributive carbon tax, which has been presented by Policy Exchange last year in the UK and has strong support from many economists, is unfortunate.

The SNP and Plaid Cymru focus on the importance of taking forward projects in their own countries (e.g. the Swansea Bay and other tidal lagoons in the case of Plaid Cymru). Their manifestos recognise that in the absence of full Scottish and Welsh independence or increased powers of the devolved Scottish and Welsh administrations in respect of energy and climate change matters, the most they can do is to apply pressure to the new UK government. For example, the SNP manifesto includes a “demand” for the “ring-fencing of oil and gas receipts [i.e. taxes on oil and gas companies currently paid to the UK government], creating a Net Zero Fund, to help pay for the energy transition through investment” in areas such as renewables, EVs and CCUS.

Beyond 12 December

It is not our job to rank what the parties have said about their intentions in relation to energy and climate change matters, or to try to use the manifestos as a basis for predicting whose proposed programme would be most likely to succeed in achieving the CCA 2008 net zero target. In any event, election manifestos are not usually detailed statements of policy, and what these manifestos say about energy and climate matters is generally no exception to that rule.

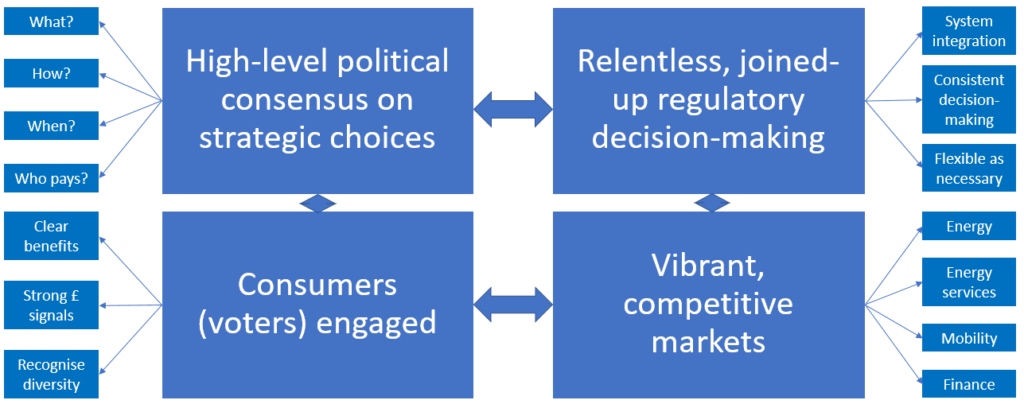

However, we do offer a view on what the key elements of any future government’s plans for achieving a net zero target must include, and this is summarised in the diagram below.

High-level political consensus on strategic choices: You need to start with clear objectives that command support across a sufficiently broad base. It’s important to be ambitious, and for those ambitions to be consistent with the net zero target. But most net zero policies will need to be delivered across the lifespan of multiple Parliaments, and the best way to enable their implementation to survive changes of government is if they command a good measure of cross-party support in the first place. Clear answers to all the questions highlighted at the side (top left) of the diagram (what/how/when/who pays?) is essential, and the more controversial those answers are likely to be, the more you need to have an honest debate about them at the outset. (There are obvious parallels here with the debate over funding social care in the long term.)

Relentless, joined-up regulatory decision-making: Turning high level net zero policy into regulation isn’t easy.

- Everything in the energy sector interacts with everything else, often in unexpected ways.

- The regulatory regime, particularly as embodied in licences and industry codes, has become almost impossibly complex, and is seen as being a barrier to innovation. BEIS and Ofgem have now acknowledged this, but the scope of possible reforms is still unclear and it is going to take a number of years, at least as regards industry codes.

- Increasingly, net zero regulation has to embrace things and organisations that aren’t subject to energy sector rules to achieve results: data ownership (and monetisation), for example, or financial reporting of climate risks – not to speak of car ownership, planting trees and not eating beef.

- Overall policy consistency is crucial (and harder to achieve than it sounds), but inevitably there has to be room to be flexible on some points over time.

- Some would argue that neither the statutory duties of Ofgem as regulator of the downstream gas and electricity sectors, nor the remit of the Oil & Gas Authority as regulator of the upstream oil and gas industry in the UK, are as consistent as they should be a net zero target. This point is controversial, but probably needs to be considered more deeply and transparently from a political and technical standpoint than has so far been the case.

Vibrant, competitive markets: Alongside effective regulation, the need for competitive markets also becomes more acute. Even the largely nationalised energy sector envisaged in Labour policy statements would need competitive markets (e.g. in equipment manufacture) to supply it. In the market structure that we have at present, ensuring effective competition is key to Ofgem’s mission, and there are clear indications of market failure or immaturity in areas such as the financing of energy efficiency or heat networks. Looking beyond the traditional energy market, it will be a lot easier to achieve a target of 100% new EVs when there are a good many more models to choose from than at present – but will that happen without some regulatory “encouragement”?

Consumers (voters) engaged: So far, decarbonisation has largely taken consumers for granted. As a whole, at least on the electricity side, they have had the costs of various forms of subsidy, levied in the first instance on suppliers, passed through to them (or not, if they Energy Intensive Industries). Some have been the recipients of supplier-funded energy efficiency measures. Now, we need them all to become more actively engaged in energy markets, and potentially to make some big spending decisions and lifestyle changes in the name of net zero. We can talk about showing them what the benefits are clearly and sending price signals, but will that work? Remember, these are the same people who for years didn’t switch energy suppliers when they were losing significant amounts of money by sticking with their existing provider. The winning policies will be those that are approved by behavioural scientists, as well as economists. In the end, as the arrows in the diagram suggest, it may come back to the political level: not for nothing do some now speak of the energy transition involving democratisation, alongside the more familiar decarbonisation, decentralisation and digitalisation of energy.

What next?

The party manifestos suggest that any future government will recognise net zero as a priority. All their programmes in this area will require major efforts to implement. The UK has a number of achievements to be proud of to date, such as the rapid expansion of its renewables sector and the adoption of the net zero target itself. But the scale and complexity of the challenges highlighted by the CCC’s report mean that whatever happens on 12 December 2019, there can be no room for complacency on any aspect of energy and climate change policy.

This post was prepared with the assistance of our London Energy team solicitor apprentice, Megan Goacher.

We are running a series of events to discuss net zero policies and their impact on energy and related sectors during 2019-20. Please get in touch with the author or join the Dentons Net Zero Energy Community on LinkedIn if you would like to learn more about these events.