One of the problems faced by the UK in achieving security of electricity supply at an affordable cost is its comparatively low level of interconnection with the electricity networks in other countries. But recent developments offer some prospect that the UK may become a bit less of a “power island”.

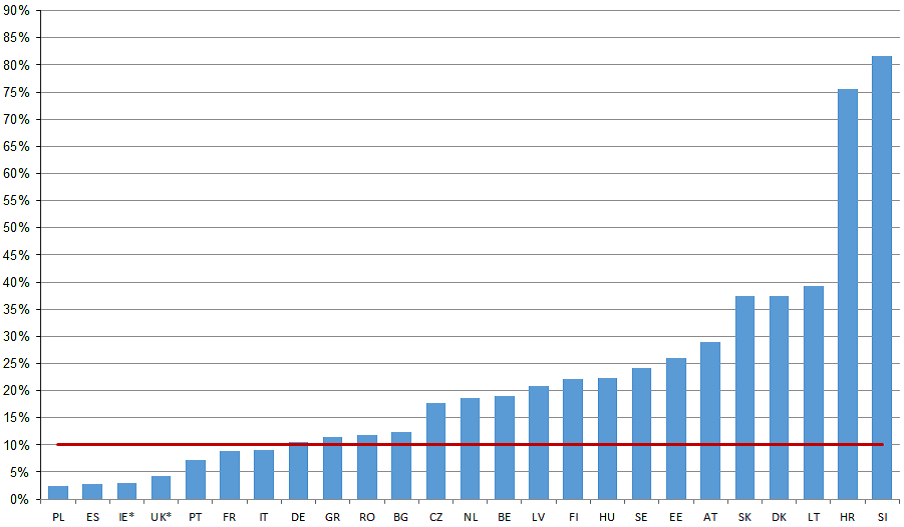

The EU’s goal of a single electricity market has the potential to help national Governments with all three horns of the energy trilemma (how to maintain security and decarbonise whilst keeping energy prices at a reasonable level). But it cannot be realised without adequate interconnection capacity. As long ago as 2002, the European Council set EU Member States a target of having electricity interconnections equivalent to at least 10% of their installed production capacity by 2005. Twelve years on, the UK is only half way to meeting this target. In May 2014, as part of its work on European energy security, the European Commission proposed an interconnection target of 15% for 2030. This was adopted by the European Council in its 23 October 2014 conclusions on the EU’s 2030 Climate and Energy Policy Framework.

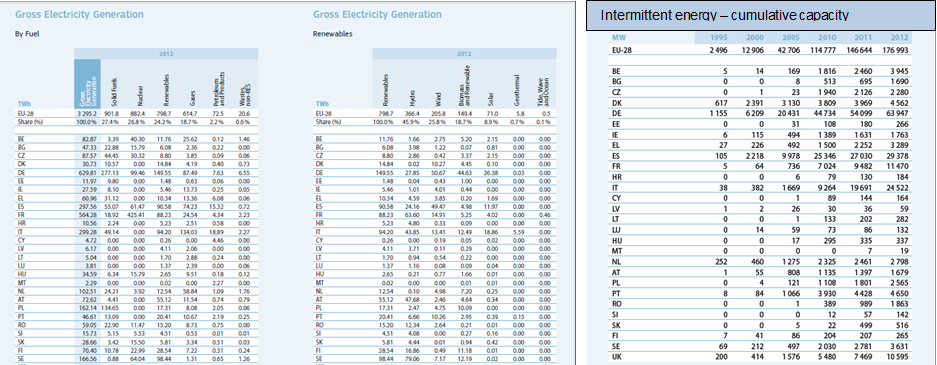

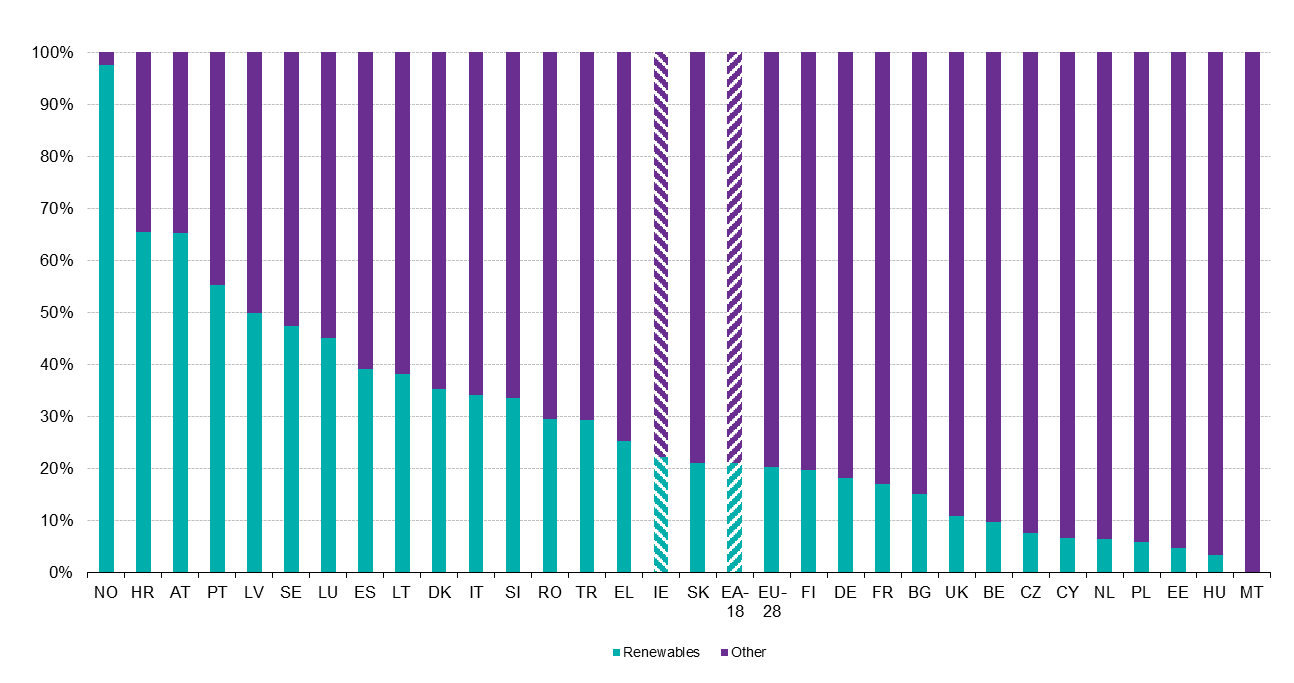

Meanwhile, as Member States connect increasing amounts of intermittent renewable generating capacity to their networks, leaving them in some cases with total generating capacity that is much greater than the amount of power they can reliably generate at any given moment, the goal of achieving 10% or 15% of total installed generating capacity becomes more challenging (see the statistics and charts below). While such targets are undoubtedly useful, the optimum proportion of interconnection capacity is not the same for each Member State and is bound to change over time with the evolution of its generating mix and electricity consumption profile. However, it is not always easy for the market to respond quickly and produce more interconnection capacity where it is most needed given the amounts of capital and the regulatory processes involved.

Achieving an interconnection target of 10% or 15% of installed generating capacity in the UK is particularly challenging. Even before it began to add significant amounts of renewable generation, the UK had one of the larger generation capacities in the EU, and it is very much more expensive per MW to create connections between the electricity networks of Great Britain and other EU Member States than it is to connect networks between Member States which share a land border. The costs per km of a subsea cable connection are several times greater than those of an overhead transmission line, and the distances involved in GB interconnectors tend to be larger than those which link the transmission systems of different countries in Continental Europe.

However, if the costs of interconnection are significant, so too are the potential benefits for UK consumers. In a paper entitled Getting more connected published earlier this year, National Grid estimated that: “each 1GW of new interconnector capacity could reduce Britain’s wholesale power prices up to 1-2%…4-5GW of new links built to mainland Europe could unlock up to £1 billion of benefits to energy consumers per year“. As the European Commission’s most recent report on energy prices and costs in Europe notes, in some of the countries to which the GB system either is not yet connected or with which it could be much more interconnected, average baseload wholesale electricity prices are up to 40% lower than those in the UK.

So is the potential for new UK interconnection capacity going to be exploited anytime soon? There are encouraging signs both from a regulatory point of view and in terms of actual projects.

The regulatory treatment of projects is crucial to the development of more interconnection. In this respect, there have been a number of helpful recent developments for potential UK interconnectors.

- In August 2014 Ofgem confirmed its intention to implement, with only minor modifications, its previously consulted-on proposals for the regime that will apply to the regulation of near term GB interconnector projects (i.e. those expecting to be commissioned by the end of 2020 and likely to be taking significant investment decisions in 2015). Ofgem recognises that if the development of new UK interconnection capacity is left to proceed without any form of regulated “consumer underwriting”, it is likely that insufficient new capacity will be built. It therefore proposes a 25 year regulatory regime of a “cap and floor” on revenues, based on its assessment of the need case and efficient level of costs for projects. The new regime, building on Ofgem’s approach to the Project Nemo interconnector, aims to combine advantages of both the traditional regulated revenue model and more purely market-based approaches. Ofgem’s 27 October 2014 consultation on the Caithness Moray transmission project shows how far a regulator’s assessment of efficient costs for a project involving subsea cables can vary from a developer’s estimates.

- Also in August 2014 the UK Government published a paper entitled Contract for Difference for non-UK Renewable Electricity Projects. This raises the prospect of Contracts for Difference (CfDs) under the Energy Act 2013 being competed for by and awarded to renewable electricity generating projects outside the UK by 2018. This is a significant step, given the continuing importance of subsidies for the renewables sector (and coming as it did shortly after the approval by the Court of Justice of EU Member States’ historic tendency not to extend their national renewables support schemes to generators in other Member States – notwithstanding the potential for such restrictions to impede free movement in the single market for electricity).

- In September 2014, the Government included in a consultation on supplementary design proposals for the Capacity Market established by the Energy Act 2013 an outline of how interconnector owners could participate in future Capacity Market auctions. This had been promised in the context of obtaining state aid clearance, so as to ensure that the Capacity Market, like similar measures being put in place by other Member States, does not militate against the integration of national markets – clearly a matter of concern to the European Commission.

- Interconnection is most effective when the interconnector capacity is allocated most efficiently and facilitates the flow of electricity from areas of lower to areas of higher prices (see study on this). These outcomes should be brought closer by the progress there has been in integrating EU national electricity markets through the Target Model. In February 2014, the markets in GB and 14 other EU Member States became part of the day-ahead price coupling regime for North-West Europe (and in May 2014 they were joined by Spain and Portugal). In April 2014, a number of Central European Transmission System Operators, National Regulatory Authorities and Power Exchanges signed an MoU to develop flow-based market coupling, which in time will enable better calculation of the network capacities that are allocated through the price coupling process.

- Finally, the 2013 EU Regulation on cross-border infrastructure (“projects of common interest” or “PCIs”, which are to be fast-tracked through national consenting processes) should make it easier to get interconnection projects funded and built.

In terms of actual projects, Ofgem’s October 2014 preliminary decision on eligibility of projects to benefit from the cap and floor regime identifies five projects that aim to commission by 2020 and, having come forward in the first cap and floor application window, have been judged sufficiently mature to proceed to the three to six month initial project assessment stage.

The five projects are: FAB Link between GB and France; Greenlink, between GB and the Republic of Ireland; IFA2, between GB and France; NSN, between GB and Norway (recently granted a licence by the Norwegian Government); and Viking Link, between GB and Denmark.

According to Ofgem, these projects, together with Project Nemo and the Channel Tunnel-based ElecLink, could add up to 7.5GW of interconnection – more than doubling existing GB cross-border apacity. They have a number of points in common. A number of these projects feature in the ENTSO-E Ten Year Network Development Plan and the European Commission’s list of PCIs. Most of them involve the Transmission System Operators of one or both of the countries they would run between or companies affiliated to them. Establishing links between GB consumers and renewable generation outside GB is an important part of the rationale for many of them (the FAB Link project even involves plans for up to 300MW of electricity generated from the tides around Alderney). Recent publicity for the TuNur project to export large amounts of solar-generated electricity from North Africa to Europe, including the UK, shows the scale of the possibilities in this area.

It now remains to be seen whether the further development of the Government’s proposals on non-UK renewable and interconnected capacity – and perhaps more significantly the outcomes of the first CfD and Capacity Market auctions (which will not be open to interconnected / non-UK capacity) – will enhance or detract from the business case for these projects.

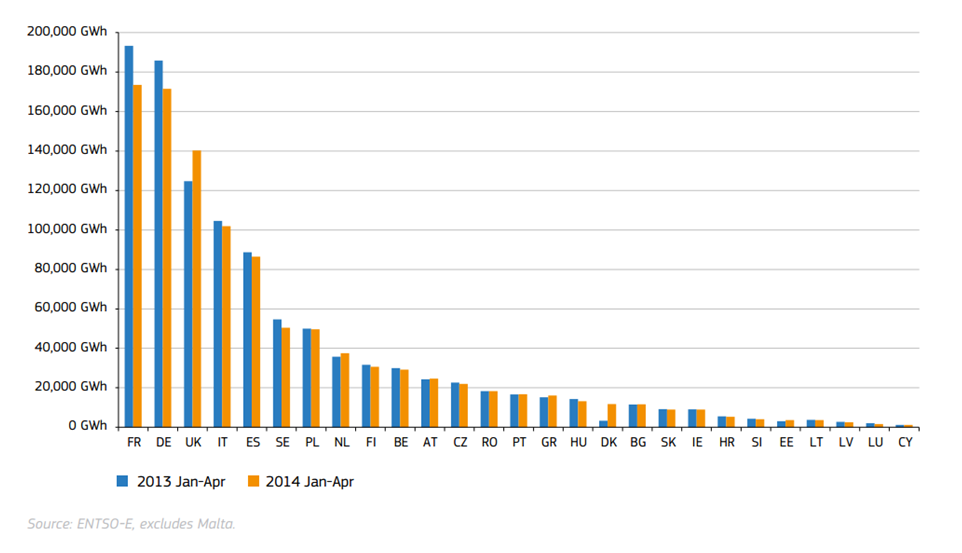

Illustrative statistics and charts (drawn from EU Energy in Figures: Statistical Pocketbook for 2014 and other European Commission and ENTSO-E publications)

1. Ratio of available cross-border electricity interconnector capacities compared to domestic installed power generation capacities

2. Electricity generation across EU Member States

3. EU Member States’ power generation supluses and deficits compared to gross inland consumption in Q1 2013 and 2014

4. Electricity consumption across EU Member States in Q1 2013 and 2014

5. EU Member States’ renewable and non-renewable generation