Sometimes, it is worth the wait. Hydrogen enthusiasts (which, these days, means almost everyone) have been asking for some time why the UK government had not yet produced a national hydrogen strategy. After all, a lot of other countries (and the EU) did so a year or more ago. With the publication on 17 August 2021 of the UK Hydrogen Strategy (the Strategy), we have the answer. The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) took its time because it was engaging seriously with a complex task, and doing a thorough job.

Background

(We suggest that you skip this section, and possibly the next one, if you already know about hydrogen, for example by having read our earlier publications on the subject, linked at the end of this post.)

Most hydrogen produced today is used as a feedstock in industrial chemical processes, rather than as an energy vector. It is so-called “grey”, “brown” or “black” hydrogen, made from fossil fuels by processes like methane reformation, which emit CO2 and contribute to climate change. However, if made without such emissions, hydrogen could play a key part in the Energy Transition.

Adding carbon capture, usage and storage (CCUS) can greatly reduce, and eventually eliminate, these CO2 emissions. Hydrogen by methane reformation + CCUS is called “blue” hydrogen. Its sustainability depends on the success of the CCUS plant and eliminating methane emissions from the upstream and midstream natural gas industry (something that we need to do anyway).

Electrolysing water with electricity that has been produced without emitting CO2 results in zero carbon hydrogen. Hydrogen produced by electrolysing with renewable electricity is called “green” hydrogen. Inherently sustainable, its viability depends on rapid and massive scaling-up (and consequent cost reductions) of renewable electricity generation and electrolyser technology.

Zero carbon electricity can also break down methane into its constituent elements of carbon (in solid form, “carbon black”) and hydrogen (using pyrolysis, and known as “turquoise” hydrogen), without producing CO2 emissions. This is a potentially promising, but currently less developed technology.

These are not the only ways to make low carbon hydrogen (for example, nuclear power is as good as renewables as a source of carbon-free electricity), but they are the ones most widely considered.

Low carbon hydrogen is not a “silver bullet”. It is only one of the changes in energy production and use that are required to reach Net Zero greenhouse gas emissions. It is not the best (cheapest/most energy-efficient) option to decarbonise all aspects of energy use. However, there are some important things that it does, or could do, particularly well. For example, it can be used to:

- store electricity for longer periods, more cheaply, and in greater bulk than any battery;

- provide a fluid vector for transporting renewable energy by ship, between places that could not be linked by electricity transmission systems (e.g. Chile and Europe); and

- provide energy for industrial heat and transport (e.g. aviation fuel) applications that it is hard to envisage being cost-effectively electrified in the short to medium term.

What is a hydrogen strategy for?

Among the key questions for any government developing a serious hydrogen policy are:

- How do you overcome the barriers presented by the fact that low carbon hydrogen is currently significantly more costly to produce than grey hydrogen or any of the incumbent fuels/energy vectors for which low carbon hydrogen could be substituted – and, in so doing, to stimulate scaling-up of low carbon hydrogen technologies and progressive reductions in their cost?

- Since switching to low carbon hydrogen requires not just investments in new production capacity, but also the adjustment and replacement of equipment on the demand side (from new steel manufacturing facilities to new bus-refuelling infrastructure or domestic boilers), what is the best way to overcome those switching cost barriers for businesses and households?

- In the absence of a pre-existing/readily extendable network to feed into (contrast the position of the first renewable electricity generators, who could take this for granted), how is the demand risk of early hydrogen projects to be mitigated (e.g. in the case of a producer who signs a long-term contract and co-locates with a large industrial user of hydrogen, such as a refinery operator, which then ceases to trade or moves its business to another jurisdiction after a couple of years)?

- For economies with a mature downstream natural gas industry that provides the primary energy source for much domestic, industrial and commercial heating, how far – and when – should hydrogen start to replace that natural gas (starting by being blended with – increasingly, biogenic – methane in the gas grid, and in time taking over some or all of the gas network completely)?

- How do you encourage the development of hydrogen applications whose real commercial potential (e.g. in aviation fuel) is probably at least 10 years away, preferably in such a way as to secure some competitive advantage in those future markets for businesses based in its territory?

Behind, or perhaps prior to, these headline questions, there is a range of more detailed issues about building the physical and economic infrastructure for a market in low carbon hydrogen as an energy commodity. These start with the question of what will count as “low carbon” in the first place, and encompass a variety of questions about the use, or re-purposing, of existing natural gas sector commercial and regulatory models and provisions for the hydrogen economy.

The Strategy’s general approach

The UK is taking a “colour-blind”, open-minded, urgent but cautious approach to developing hydrogen policy. Like some other recent UK energy policy documents, the Strategy is as much a list of future consultations to be held and decisions to be made as it is a statement of matters already decided. However, the timescales for future action look credible and it is clear from the Strategy itself and the other documents published alongside it that BEIS’s thinking is informed by robust analysis.

The guiding principles of the Strategy and the further policies to be developed from it are: long-term value for money (VfM) for taxpayers and consumers; growing the economy whilst cutting emissions; securing strategic advantages for the UK; minimising disruption and cost for consumers and households; keeping options open/adapting as the market develops; and taking a holistic approach.

In a world where talk of multi-GW low carbon hydrogen projects is becoming commonplace, the UK’s (already announced) targets of 1GW of low carbon hydrogen production by 2025, and 5GW by 2030 could seem pedestrian. However, this misses the point. The emphasis is not on numbers-based ambition for its own sake, but on building, as quickly as is sensible, a policy and regulatory environment that – from every perspective – will allow the UK hydrogen sector to flourish in the long term.

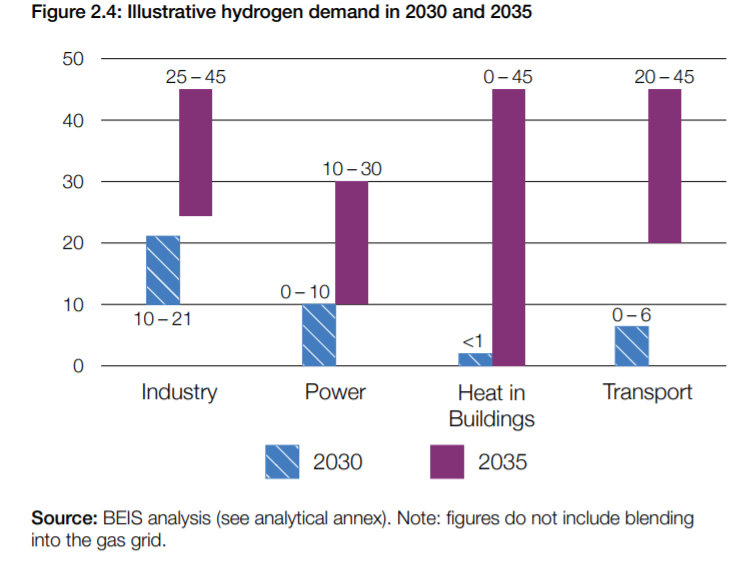

The Strategy is very focused on hydrogen’s contribution to meeting the UK’s Sixth Carbon Budget (“CB6”, covering the period 2033-2037). It notes that in most of the pathways modelled for CB6, hydrogen demand doubles in 2030-2035 and that hydrogen could supply up to a third of final energy consumption by 2050. However, taking account of uncertainty is a key feature of BEIS’s thinking: see, for example, the chart, showing ranges of possible demand (in TWh) by sector in 2030 and 2035.

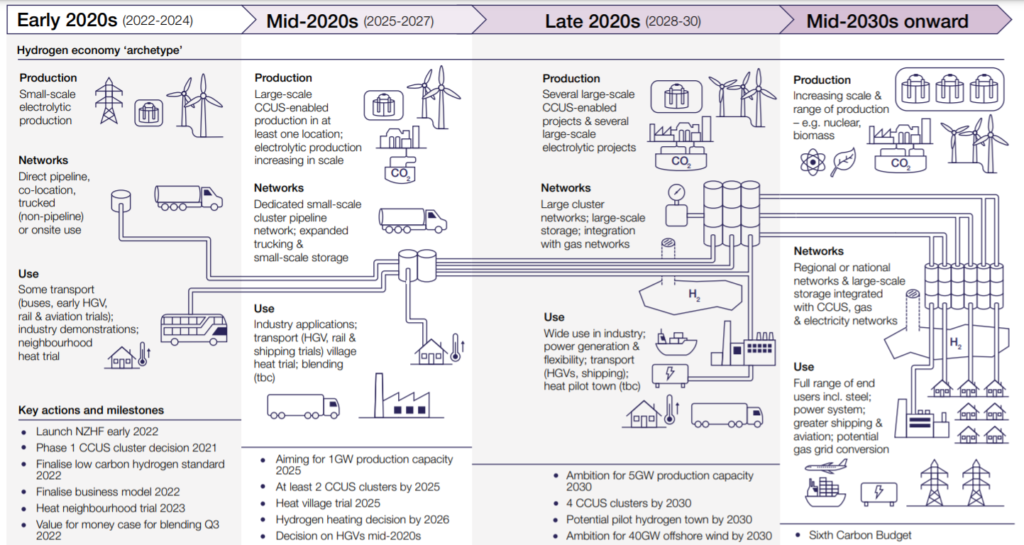

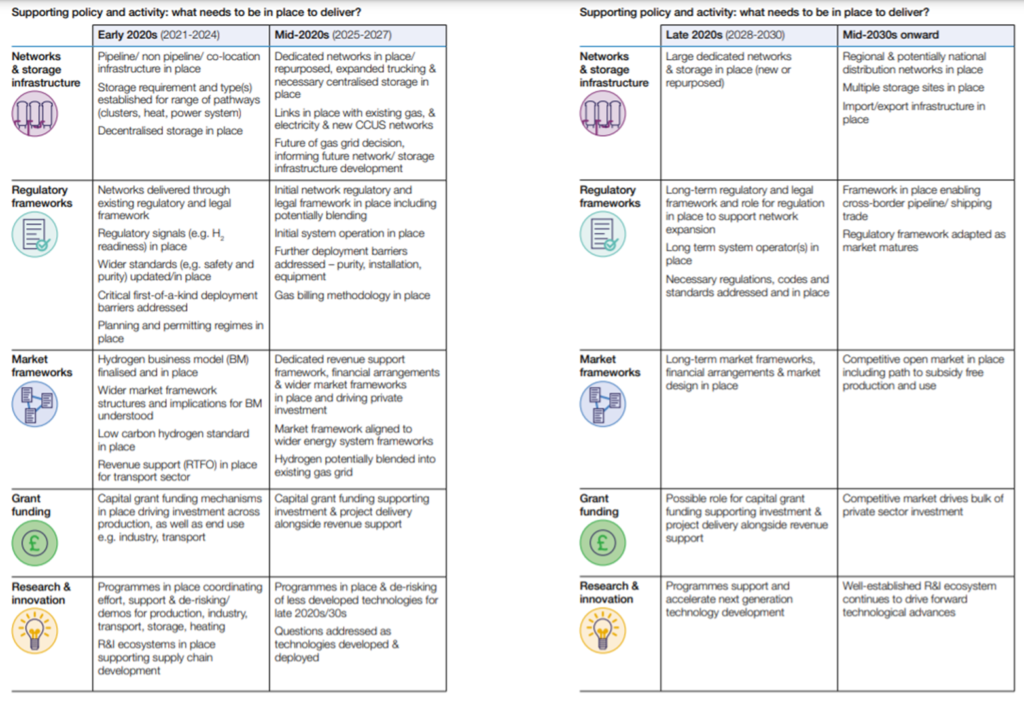

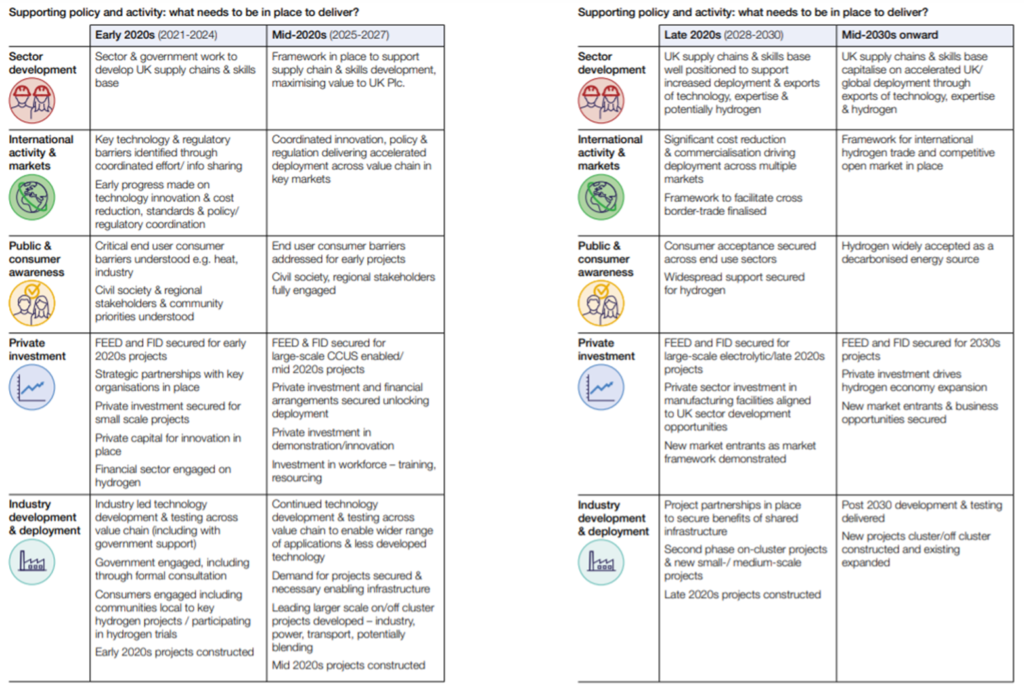

The Strategy shows an awareness of the range of government and regulatory action needed to support a flourishing low carbon hydrogen sector, but it also sets that in a bigger picture which includes international activity and the role of the private sector. This is summarised in its figure 2.1, which, because of its size, we have reproduced at the end of this article.

Answers to the big questions?

The Strategy does not pretend to have the full answers to all (or, as yet, perhaps any) of the big strategic questions outlined above. However, in the context of those questions, what it says in relation to three areas of policy is particularly notable and encouraging.

- BEIS has thought carefully about its proposed hydrogen business model (i.e. a regime of regulated financial assistance for low carbon hydrogen production), which is the subject of one of the consultations published alongside the Strategy. This aims to supplement the market price producers receive where this is lower than their costs of production. It would also address demand risk, by combining a “variable premium”, contract for difference-like price support mechanism and a “sliding scale” mechanism that would pay a higher level of price support on initial volumes, allowing the producer to recover fixed costs at relatively low offtake volumes. We will analyse the detail of these proposals elsewhere. The key point to note for now is that BEIS aims to digest and respond to responses to this consultation in Q1 2022, and to publish indicative heads of terms with that response, in preparation for allocating the first contracts under the business model in Q1 2023. This urgency is partly driven by the timetable of BEIS’s parallel CCUS programme, but the boost that the business model can provide to projects will be available to green, as well as blue, projects.

- The blending of hydrogen in the gas grid is the subject of a number of innovation projects carried out by GB gas network operators. The ability to export hydrogen in this way offers producers a potentially ideal back-stop means of mitigating demand risk, and the substitution of low carbon hydrogen for some of the methane that would otherwise be consumed by end users connected to the grid could make significant contributions to decarbonisation. In this context, it is very encouraging that the Strategy promises an indicative VfM assessment on blending up to 20% hydrogen by Q3 2022, and a final decision on it in late 2023.

- For some time now, it has been clear that there will be a strategic choice to be made on what should replace the fossil fuel methane that provides most space heating in the UK. Heat pumps powered by renewable electricity may be an ideal solution from some perspectives but, for a variety of reasons, a “mixed economy” of heat pumps and decarbonised gas-fired heating may be preferable, at least for some consumers. The Strategy sets a date (or at least a year) for taking a decision on the future of hydrogen in heat: 2026. This will be informed by the results of “neighbourhood” level trials in 2023, and “village” level trials in 2025.

Meanwhile, questions about meeting demand-side switching costs and developing the markets for future applications of low carbon hydrogen in the transport sector are partly answered by competitions for funding, details of which accompany the Strategy. These include:

- £240 million for the Net Zero Hydrogen Fund (2022-2024/25);

- up to £60 million under the Low Carbon Hydrogen Supply 2 competition;

- financial support for fuel switching (via the Industrial Energy Transformation Fund, Industrial Fuel Switching 2 Competition and Red Diesel Replacement Competition);

- up to £41.8 million on marine, aviation and other projects; and

- £140 million split between buses (£120 million) and HGVs (£20 million), shared with battery technology.

At the same time, there is ample evidence of government pursuing the key background, commercial and regulatory infrastructure issues, such as:

- reviewing the suitability of Gas Act framework and gas quality standards for facilitating a decarbonised gas future;

- setting up a Hydrogen Regulators Forum (covering regulators with responsibility for environmental, safety, markets, competition and planning matters);

- engagement with industry on optimising the benefits of early-adopting clusters; understanding the impacts of full or partial transition to hydrogen via the gas grid on industrial consumers and their needs; the possibility of a research and innovation facility to support hydrogen use in industry and power; and understanding economics and system impacts of hydrogen in the power sector.

Keeping up the pace

The Strategy and the other documents published with it (see below) are just the start. Below is a list of what the Strategy promises by way of further policy development in the coming months.

- Before the end of 2021, the Strategy promises:

- “We will set out our aspirations to continue to lead the world on carbon pricing” (in the run-up to COP26). Needless to say, this could be hugely important. A sufficiently rigorous and broad-based approach to carbon pricing has the potential to turbo-charge the development of a hydrogen economy. Might the UK extend its Emissions Trading System to sectors such as heat and transport, as the EU is proposing to do with the EU Emissions Trading System? Might it seek to incentivise energy-intensive industries not only in the UK but beyond to switch to the use of low carbon hydrogen and other cleaner forms of energy by adopting a border carbon adjustment – again, as the EU is proposing to do?

- A consultation on enabling/requiring new gas boilers to be easily convertible to hydrogen by 2026: for most consumers, this could be their point of entry into the hydrogen economy. Getting both the technical details and the messaging right is very important.

- call for evidence on hydrogen-ready industrial equipment: a precursor, perhaps, to the business-sector equivalent of the above.

- A call for evidence on the future of the gas system: clearly an important building block towards some of the key decisions for later in the decade highlighted above.

- In or by “early 2022”, the Strategy tells us to look out for:

- further detail on production strategy…including less developed methods;UK standard for low carbon hydrogen – design elements to be finalised;

- status update on hydrogen storage: review of systemic regulatory/funding requirements;

- Hydrogen Sector Development Action Plan;

- initial conclusions and proposals on identifying, prioritising and addressing regulatory barriers;

- initial conclusions and proposals on developing appropriate market frameworks.

- On a slightly more leisurely timescale (within a year), we are to expect a call for evidence on phasing out carbon intensive hydrogen and its replacement with the low carbon variety.

- Finally, the Strategy tells us that a call for evidence on “energy consumer funding, affordability and fairness” (an issue that clearly goes beyond hydrogen, but is very important to the question of how support for low carbon hydrogen is to be funded) is “expected to be published soon”.

For ease of reference/further reading

As already noted, the Strategy was not the only hydrogen policy document released by BEIS on 17 August 2021. For ease of reference, we produce links to the Strategy and all the other documents below. We will be commenting further on these in due course, as well as on the other policy documents that the Strategy promises will be forthcoming, as they emerge. If you have any questions about UK hydrogen policy in the meantime, please get in touch!

UK government launches plan for a world-leading hydrogen economy – press release.

UK hydrogen strategy: sets out the approach to developing a thriving low carbon hydrogen sector in the UK to meet our ambition for 5GW of low carbon hydrogen production capacity by 2030.

Hydrogen analytical annex: supports the policy thinking in the Strategy and other documents below.

Hydrogen production costs 2021: presents levelised cost estimates for hydrogen production technologies, detailing methodology, data and assumptions.

Consultation on a business model for low carbon hydrogen: seeks views on the design for a low carbon hydrogen business model (in other words, a subsidy/revenue stabilisation mechanism).

Designing the Net Zero Hydrogen Fund: seeks views to inform the design of the Net Zero Hydrogen Fund (NZHF), to support at-scale deployment of low carbon hydrogen production in the 2020s.

Consultation on a UK low carbon hydrogen standard: seeks views on design options for a UK standard that defines “low carbon” hydrogen, to underpin our support for hydrogen production.

Options for a UK low carbon hydrogen standard: report: sets out options for a standard that could define what is meant by “low carbon” hydrogen; has informed the consultation above.

Hydrogen for heat: facilitating a grid conversion hydrogen heating trial: seeks views on possible legislative changes to enable the delivery of a hydrogen grid conversion trial.

There are also some relevant funding competitions in the Net Zero Innovation Portfolio:

- Low Carbon Hydrogen (Stream 2): this aims to support innovation in the supply of hydrogen, reducing the costs of supplying hydrogen, bringing new solutions to the market and ensuring that the UK continues to develop world-leading hydrogen technologies for a future hydrogen economy;

- Industrial Fuel Switching competition: this will support innovation in the development of pre-commercial fuel switch and fuel switch enabling technology for the industrial sector, to help industry switch from high to lower carbon fuels: expected to launch in October 2021;

- Red Diesel replacement competition: a £40 million competition to support the development and demonstration of low carbon fuel and system alternatives to red diesel for the construction, and mining and quarrying sectors from April 2022.

Strategy Figure 2.1

The pictures below are taken from Figure 2.1 of the Strategy. It gives a good summary of BEIS’s overall vision of the roles that government and others will play in developing a UK hydrogen economy.

Links to some earlier Dentons publications on low carbon hydrogen

The prospect for hydrogen (a general survey)

Making early hydrogen projects investable (jointly written with Frontier Economics, focusing on regulated financial assistance for blue hydrogen projects in the UK context)

Scaling up green hydrogen in Europe (jointly written with ILF and Operis, including linked webinar)

The Oil and Gas Authority’s Net Zero Goals; Hydrogen

Blending hydrogen in the GB gas grid (two articles, here and here)